Black Arts Movement Artists

To response to the ideology of

Black Power, Black Arts

Movement, as opposed to artwork simply created by an African American artist,

signified the only relevant artistic production in the struggle for African

American self-determinacy. Therefore, Black Art rejects the "art for art's

sake theory" in favor of advancing art's sociopolitical influence in the

re-definition of African American identity. Black artists, aimed to challenge

the white standard aesthetic value system, voiced their

own black culture and express ideas from the point of view of racial and ethnic

minorities was not valued by the mainstream to display the distinction of black

identity. Like other

Black Art Movement activists, Toni Morrison internalizes the main concerns of

the aesthetic. She writes about black oppression, consciousness and tradition.

Morrison’s major characters are black and they are in constant search for their

ethnic identity. Morrison tackles the destructiveness of double-consciousness

in The Bluest Eyes. She does not

avoid painful and complicated themes in her novels about black experience, and

she also chooses stylistic devices that are faithful to her African-American

heritage. Morrison implicates the importance of her culture by reflecting black

traditions of storytelling and black spoken dialogs. Similar to Morrison, black

artists in BAM displayed the ideologies and perspectives of art that center on

black culture and life, and strengthen black ideals, solidarity, and

creativity. They against the institutional

racism that through educational system, popular culture and production of items

that only cater to the whites. Black artists tried to open a new era that gives

more space to individuality and diversity and against the community as a whole

has accepted the Western values and considers differences from it a flaw. In

Morrison’s The Bluest Eyes, Pecola

and Claudia remain a meaningful contrast to each other in facing the problem of

Eurocentrism.

Aunt Jemima and the Pillsbury

Doughboy, 1963

Aunt Jemima and the Pillsbury Doughboy, a Jeff Donaldson’s oil painting, portrays

the confrontation Donaldson envisioned. Appropriating icons of American

consumer culture, the painting not only portrays a confrontation between Aunt

Jemima and the Pillsbury Doughboy, but also enacts a confrontation with popular

media imagery responsible for furthering racist stereotypes. Donaldson's

depiction of Aunt Jemima subverts the docility and subservience associated with

this image of black womanhood. Though the Pillsbury Doughboy (a figure of

oppression in the painting) restrains Aunt Jemima, her defensive stance and

fierce expression indicate that she will not concede defeat. Moreover, Aunt

Jemima’s statuesque figure implies that she holds the upper-hand in a contest

of strength with her oppressor. Pitting The Pillsbury Doughboy against Aunt

Jemima, Donaldson is simultaneously “identifying the enemy” and asserting black

America's strength to overcome racist oppression and challenge the power of

white supremacy. Notably, the subversive nature of Aunt Jemima and the Pillsbury Doughboy extends to the American

flag as well. The strips of the flag in the painting's background are bent in

an angle reminiscent of a swastika. Challenging the notions of democracy and

freedom associated with the American flag, Donaldson is drawing a jarring

connection between American racism and the recognized atrocities of Nazism

since the destructiveness of the white beauty standard to the African American

community is significant. The most notable victim is Pecola in Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eyes, who is deeply affected by the illustrations

of white beauty around her

and believes that she is ugly and desires to “be Mary Jane,” becoming insane at

the end due to the society’s assuming of her ugliness. The Black Arts

concepts struggled to abandon Du Bois’s idea of double-consciousness since blacks

were constantly struggling toward the white culture’s ideals, even though the

dominant society disabled them from reaching the white standard of beauty.

Mirroring themselves against value structure of the oppressive white society

was depriving the blacks of their empowerment. Jeff Donaldson wanted to concentrate on solving the

problems of the African-American community from the inside, developing

awareness of the rich black heritage and gearing the community to realize its

worth. The Black Art Movement leaded the time for blacks to stop internalizing

the image of being inferior in the society as a whole and asserting the strength,

beauty, and self-esteem of blacks. Preventing the tragedy of Pecola, black

artists built up black’s own brand—Aunt Jemima to confront the white standard

beauty figures of “Mary Jane” and “Shirley Temple”. Jeff Donaldson claimed the

"next level of struggle would [have to be] confrontational," to be

black themselves and to love themselves, but not to “be Mary Jane” and “love

Mary Jane” (50).

The Black Art movement leaders tried to liberate blacks from the limitation of

white beauty standard and the fallacy that people’s value depend on their

looks.

Polarization, Claude Clark

Polarization presents the condition, names the

enemy, and directs a plan of action. Depicting a black man arm wrestling Uncle

Sam, Claude Clark presents African American life in

opposition to white America; he specifically identifies the American government

as the "enemy," and he points to direct confrontation as the mode of

socio-political struggle. While Polarization portrays a confrontation

still in action, Clark's iconography foreshadows the "American"

victor. Linking African American's struggle for civil rights with the American

Revolution, the American flag placed on the "side" of the black man

indicates his eventual victory over the "monarchy" of white America (the

crown beneath Uncle Sam's bench). Toni Morrison reveals the destructiveness of

white authority by excerpting sentence from Dick

and Jane. Like

Uncle Sam, Dick and Jane are also the creations of the white society that

determines the material values and desirable appearance for everyone. The

blacks do not have public representation in the society. There were no reading

assignments about black children who live in poverty. This manifestation of

institutional racism contributes to the black characters’ personal prejudices,

increasing their feeling of insecurities and ugliness. The Black Art Movement aimed

to change black’s situation by fight against the standard aesthetic value set

up by white people and “towards a plan of action in search of our

own roots and eventual liberation" (Claude Clark).

This painting is an assertive revision of

African American poet Paul Laurence Dunbar's most noted poem "We Wear the Mask."

We Wear the Mask

Paul Laurence Dunbar

Paul Laurence Dunbar

We wear the mask that grins and

lies,

It hides our cheeks and shades our eyes,--

This debt we pay to human guile;

With torn and bleeding hearts we smile,

And mouth with myriad subtleties.

It hides our cheeks and shades our eyes,--

This debt we pay to human guile;

With torn and bleeding hearts we smile,

And mouth with myriad subtleties.

Why should the world be overwise,

In counting all our tears and sighs?

Nay let them only see us, while

We wear the mask.

In counting all our tears and sighs?

Nay let them only see us, while

We wear the mask.

We smile, but O great Christ, our

cries

To Thee from tortured souls arise.

We sing, but oh, the clay is vile

Beneath our feet and long the mile;

But let the world dream otherwise,

We wear the mask.

To Thee from tortured souls arise.

We sing, but oh, the clay is vile

Beneath our feet and long the mile;

But let the world dream otherwise,

We wear the mask.

As depicted

in the painting If I Were Jehovah, the "mask" African

Americans historically used to shield the depth of their emotions in a racist

society is being ripped away in a full expression of outrage and determination.

The “mask man” in the painting rejects the white authority and tries to abandon

the double-consciousness. Similar to Claudia in Morrison’s The Bluest Eyes, the “mask man” does not wish to

be white, but hate the western ideal and “desires to dismember it” (20). The “mask

man” and Claudia recognize the institutional racism around the: the mass media

bombards the black community with white images of beauty, making it harder for

the minority to maintain its own identity and worth since no public

presentations of black ideals or role models are available. Like Claudia, the

activists in the Black Art movement rebelled to white institution and took off

black’s mask.

Black artists in the movement tried to distinct black

culture by using African motifs and musical beats in their art works, and they have

profoundly changed what and how America sees--in the images that flare on the

canvas as well as those that flicker on the large and small screen.

Gordon Parks

peeked through photographic and cinematic lenses to

record the travail of Black life. In the photo “Children with Doll,” the two

children represent different attitude to the white doll, just like Pecola and

Claudia in The Bluest Eyes. One is

addicted to the white doll and wants to become white girl, and one hates and

rejects white standard beauty. While

Pecola drowns herself of ugliness and worthiness and becomes a victim of the

white standard of beauty, Claudia rejects the western ideal and in somewhat

rebels like the Black Art movement activists.

Black artists used Abstract Expressionism and social

protest--and brushes, pens, invented materials and found objects--to fashion

the textures and colors of a new Black humanity that challenged racial

stereotypes.

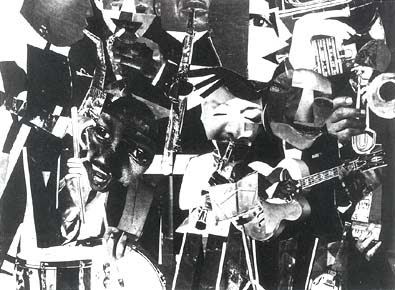

Jazz:

(N.Y.) Savoy--1930s,

Romare Bearden

Humanity shines in Romare Bearden's

collage, Jazz: (N.Y.) Savoy-1930s, which treats the most majestic music Black

folk have created. Bearden achieves the sense of sound and rhythm associated

with jazz through irregular spatial relationships and intense lights and darks.

As in the music, what appears random—a face here and instrument there—coheres

into a structured whole. To

portray black ethnic voice like Bearden does, Toni Morrison uses old, black

storytelling traditions in The Bluest

Eyes to convey an authentic African-American experience. Morrison uses the

call-and-response style of communication that initiates from the time of slavery.

She continuously changes her focalization with narrative and writes

non-chronological revealing of Pecola’s story, aiming to resemble

African-American storytelling. Through the methods of black storytelling,

Morrison gives a voice to several silenced issues of oppression.

Black

artists and writers like Toni Morrison in Black Arts Movement were both trying

to challenge the authority of white value system and injecting new diverse

voices of minority. Their rebellion not only dealt with the racial issues but

also changed the dominant white culture situation to a new multicultural era.